Researchers at the McMaster Injury Biomechanics Laboratory are making sport safer by evaluating the protection of hockey neck guards – an overlooked area in the sportswear industry.

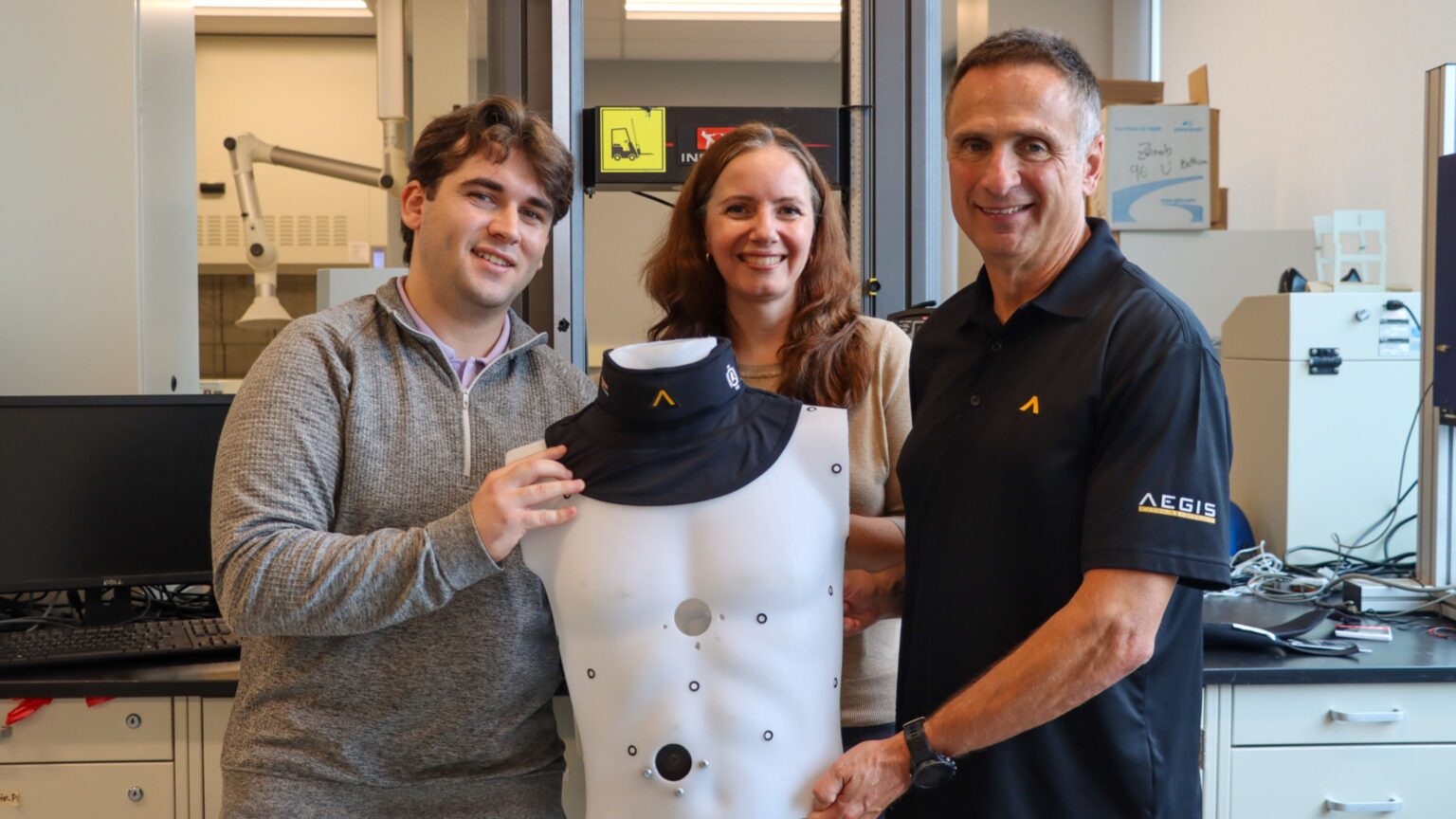

The group, led by Faculty of Engineering associate professor Cheryl Quenneville, is pioneering new ways to assess how much neck guards protect against puck impact.

They’ve partnered with Niko Apparel Systems, whose AEGIS Impact Interceptor neck guard is unique in the arena of hockey equipment; it’s the first of its kind to be designed for impact attenuation. Other commercial neck guards, Quenneville says, don’t consider this type of thinking; the equipment is primarily designed for slicing injuries, which leaves a huge gap in protection.

“There have been injuries due to puck impact with really devastating outcomes,” Quenneville says.

There are currently no standards in the hockey apparel spectrum on how to evaluate most equipment – with exceptions such as helmets – meaning a commercial-wide reliance on “chunky padding”, she explains.

“The long-term goal is hopefully to change the field of hockey apparel so that not just helmets and face guards are part of impact test standards,” Quenneville says.

Drastic differences in attenuation

Quenneville’s lab team is bringing a ballistic defense background and experience in automotive applications to the athletic sphere.

Mechanical engineering undergraduate students developed the surrogate – a mannequin with force sensors and spring assemblies to mimic the human body – as part of their capstone project. It was mounted in a pneumatic impactor with a puck as the projectile.

Researchers examined two key areas of the body – the neck and the collarbone, which are both vulnerable to injury in hockey – and assessed how much energy was absorbed by different materials.

There was a wide range in performance, with the materials varying between a 13 per cent and 46 per cent reduction in force transmitted to the collarbone area.

As well, not all foams tested recovered from the blow, meaning their ability to protect the body would be drastically reduced after a first impact.

The AEGIS Impact Interceptor neck guard was the exception – it functioned extremely well and didn’t decrease in performance with repeated shots, says Quenneville.

Data showed the AEGIS Impact Interceptor neck guard performed over 30 per cent better in attenuating than other big-name brands – an amount that Quenneville says can have a substantial effect on an individual’s health outcomes.

The data will help Niko Apparel Systems determine which foams to pursue to best protect the players.

“It was exciting to see that there there’s a lot that can be done by selecting the right materials to protect people,” Quenneville said.

Quenneville’s lab will continue investigating variables such as puck speeds, alternate locations on the body, and the effect of washing on materials and how that might degrade materials over time.

Joe Camillo, owner of Niko Apparel Systems and founder of Aegis Impact Protection, stressed the importance of partnering with the lab to increase safety in sport. He drew inspiration as a father of four children who all played minor hockey in Hamilton while growing up.

Improving safety and offering the best possible protection has always been our goal.

‘It will change the culture’

For PhD student Carson Brewer, the opportunity in the McMaster Injury Biomechanics Laboratory merges his personal interest in hockey and doctoral work on reducing injuries due to automotive collisions. This work not only revealed current hockey players’ vulnerability, Brewer says, but also provided him the chance to make a difference by identifying existing materials that provide more protection.

“The potential for this work to inform change in the current neck guard standards, to require impact protection in their design, is really important, as that is the necessary step to ensure hockey players are adequately protected,” he says.

Consideration of neck guards, primarily as a result of slicing injuries, garnered worldwide attention in 2023 following American hockey player Adam Johnson’s death. In Canada, junior hockey leagues that didn’t already require this equipment changed their requirements. Less than two months later, a puck struck the neck of a minor league player in Quebec; though he wore the required protective equipment, the 11-year-old player tragically lost his life.

While professional leagues like the NHL and PWHL said they would re-evaluate rules, they have not yet mandated this protection.

Public education about safety equipment is of immense importance, Quenneville says. She noted that while incidence of these events is low, their implication is substantial.

That makes this data crucial, she says. Her hope is that neck guards become second nature for young people, like bike helmets for children.

“If we can clearly show leagues and parents that players need this, it will change the culture to one where it becomes a default,” she says. “While young players might not yet see the stars they idolize wearing this protection, the results will hopefully positively influence them. Working with a company that wants to follow science to improve protection is very inspiring.”