Throughout her years as an engineer and researcher in cardiovascular mechanics, Zahra Motamed says her goal has always been to save lives.

“My grandfather had heart failure with other diseases, and he wasn’t able to tolerate the surgery,” she says, recalling his passing just 10 days after his heart surgery.

“What if physicians had a tool that takes into account a patient’s complex medical history, and predicts which treatment would work best long-term?”

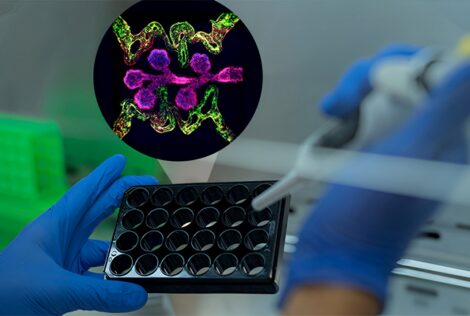

Now, Motamed leads an interdisciplinary team in developing this novel technology for patients with aortic valve disease. The tool will help medical teams predict the outcomes of specific medical interventions for each patient.

“What might work for one person with heart disease may be harmful for another, and children and older patients are especially vulnerable,” says Motamed, an assistant professor in mechanical engineering.

This tool will overcome critical obstacles in saving lives by accurately testing how effective an intervention will be before it’s performed irreversibly on the patient’s body.

It’s one step closer to making personalized medicine possible for people with heart disease, she adds.

The project recently received $780,000 in funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) to advance the technology.

Motamed’s team is currently developing the tool for aortic valve disease, which is one of the most common and serious cardiovascular problems. It’s characterized by damage to or a defect in one of the four heart valves.

Upon successful launch of this tool, Motamed says her team will expand the scope of the predictive tool to address other cardiovascular diseases and devices.

It also has potential to help companies making medical devices for people with cardiovascular disease.

“This tool will also be crucial for developing, validating and optimizing new cardiovascular devices, such as transcatheter valve replacement, an emerging and minimally invasive device for patients with aortic valve disease,” she says.

“It allows performing important in vivo evaluation routines in vitro and therefore reduces the need for animal testing and human trials, reducing the time-to-market and cost-to-market for new products. Currently, in absence of such a technology, these companies heavily rely on animal testing and human trials.”

Key clinical collaborators on this project include Drs. Javier Ganame (cardiologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare and Hamilton Health Sciences, McMaster University), Jonathon Leipsic (Canada Research Chair in Advanced Cardiopulmonary Imaging at St. Paul’s Hospital, UBC), José M de la Torre Hernández (interventional cardiologist and Chief of Interventional Cardiology at Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Spain), and Maureen MacDonald (Dean of Science, McMaster University).

Motamed calls these clinicians the “key to success” for continuously advising her team on how to make the tool as clinically relevant as possible, and providing de-identified and anonymized clinical data.

“They’re the end user of what we’re developing,” she adds. Early in her research, Motamed also collaborated with congenital disease cardiologists at Massachusetts General Hospital and MIT.