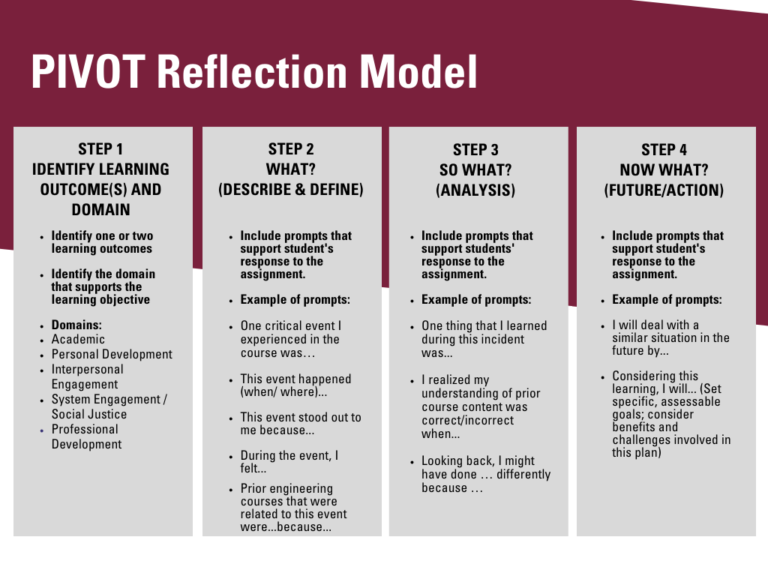

The McMaster Engineering Reflection Model represents the framework used for Engineering Pivot course reflections and capstone courses, is adapted to integrate elements of the What? So What? Now What? Framework with Ryan’s and Ash & Clayton’s models. From Ryan’s model, we refined the What? component to direct student focus to a critical incident of the experience to center their thinking on one important incident rather than on considering the entire experience. From Ash and Clayton’s model, we focus attention on the importance of aligning reflection assignments to learning outcomes by identifying the appropriate domain. Through this alignment, we can best assess students’ achievement of the intended outcomes.

Sources:

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., & Jasper, M. (2001). Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions a User’s Guide. Palgrave.

Borton, T. (1970). Reach, touch, and teach (pp. 75-91). New York Mcgraw-Hill.

Driscoll, J. (1994). Reflective practice for practice. Senior Nurse, 14(1), 47-50.

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1(1), 25-48.

Ryan, M. (2013). The pedagogical balancing act: Teaching reflection in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(2), 144-155.

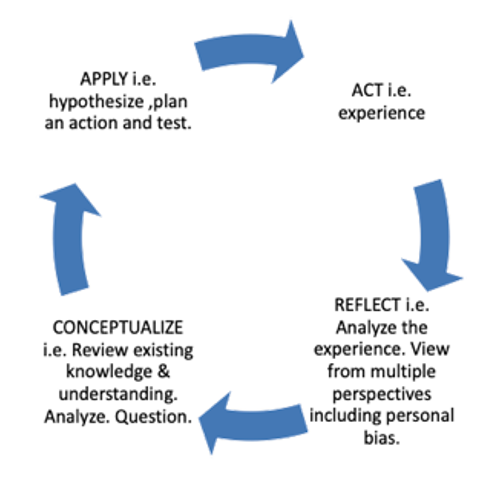

Each model of reflection closely follows the cycle of Experiential Learning as conceptualized by David Kolb (1984). Through thoughtfully crafted prompts, structured reflection assignments walk students through each component of the cycle. Reflection assignments are intended to support students to think through and articulate the process of applying theory to practice and generating meaning from what they learned from this experience. In this way, students have the experience AND don’t miss the meaning.

Sources:

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

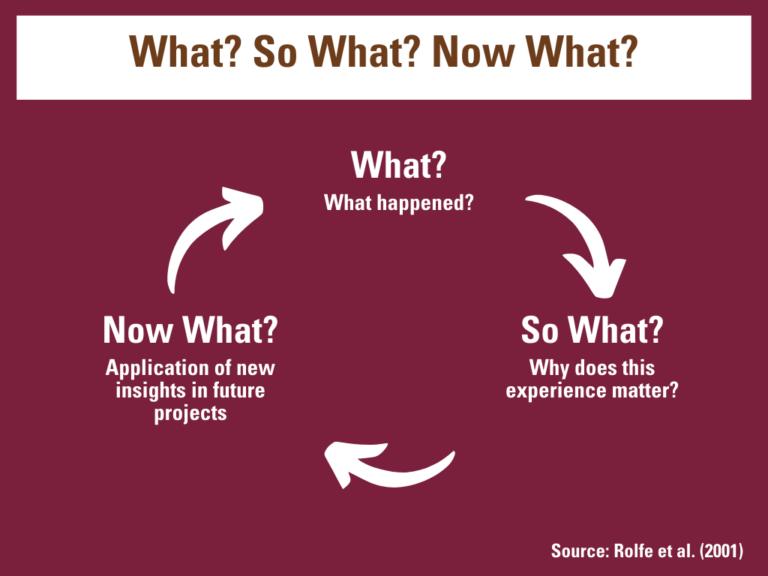

A straightforward framework, and the basis for reflection assignments in Engineering PIVOT courses (see PIVOT Reflection Model). First developed by Borton (1970) and built upon by Driscoll (1994) and Rolfe (2001), this framework is easy to use and adapt to your own course.

What? (What Happened?)

Students describe what happened and how they felt during this part of the experience.

So What? (Why is this important? Why does it matter?)

Students delve deeper into finding the meaning of the experience by examining why this experience matters. Students grapple with what may have been unexpected, unpleasant or misunderstood. As well, students may explore the importance of applying theory to practice successfully and what this means for their understanding of the situation.

Now What? (How will students apply their learning to a future experience?)

Students create a plan for experimenting or applying this new knowledge in the future.

Sources:

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., & Jasper, M. (2001). Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions a User’s Guide. Palgrave.

Borton, T. (1970). Reach, touch, and teach (pp. 75-91). New York Mcgraw-Hill.

Driscoll, J. (1994). Reflective practice for practice. Senior Nurse, 14(1), 47-50.

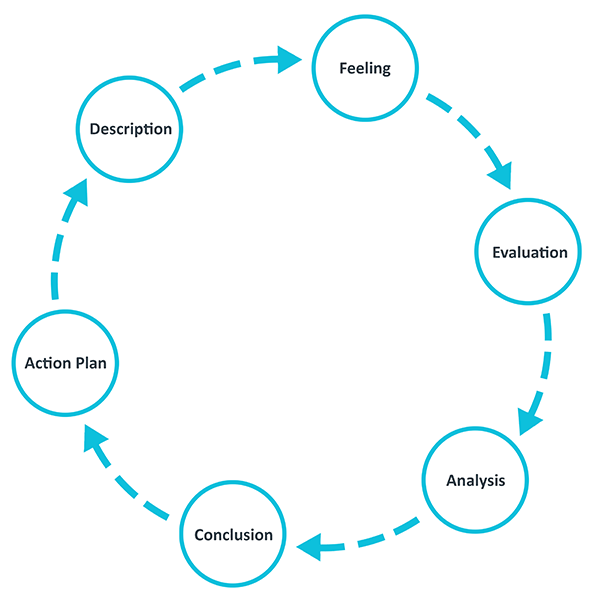

Gibbs (1988) outlines six steps in the reflective cycle, encouraging students to work through the process (whether it was a good or challenging experience) from describing an event to developing a plan for applying their learning to future experiences.

Gibb’s Reflective Cycle. (2020, November 11). The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from https://www.ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle

- Description of the experience

- Feelings and thoughts about the experience

- Evaluation of the experience, both good and bad

- Analysis to make sense of the situation

- Conclusion about what students learned and what they could have done differently

- Action plan for how students would deal with similar situations in the future, or general changes they might find appropriate

This information was adapted from The University of Edinburgh – Reflection Toolkit website. For more information, please see the following link: https://www.ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle

Sources:

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. Birmingham: SCED.

Gibb’s Reflective Cycle. (2020, November, 11). The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from https://www.ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle

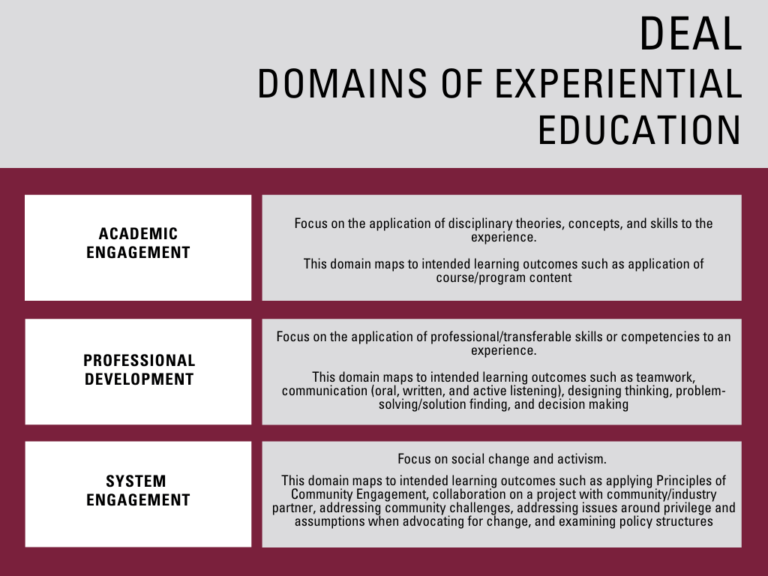

Ash and Clayton’s DEAL Model (2009) provides three steps that help align the experience with learning outcomes for the course. Like most reflection models, it encourages students to look ahead at how they may apply what they have learned to similar experiences in the future.

- Description of the experience in an objective and detailed manner

- Examination of the experience in light of learning goals/objectives

- Articulation of Learning, including goals for future action

The DEAL model suggests identifying the domain(s) that best support the learning objective of the course or component upon which to focus reflection assignments.

Sources:

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1(1), 25-48.

Ryan’s 4 Rs Model (2013) (adapted from Bain et.al. 2002) provides a reflection model that supports students as they learn how to reflect through well formulated prompts designed to guide students’ thinking through each step. The focus of each level is on leading students toward a deeper understanding of their experience and applying their learning in the future.

- Reporting and Responding: Report what happened by identifying one impactful/critical incident. Students form personal opinions around their experience in an emotional response.

- Relating: Relate incident to skills, professional experience or discipline knowledge. Students make connections between prior knowledge/skill and the new experience.

- Reasoning: Reflection moves towards an intellectually rigorous analysis using literature. Students connect relevant scholarly work/theories to practice.

- Reconstructing: Plan for moving forward for future practice.

Sources:

Ryan, M. (2013). The pedagogical balancing act: Teaching reflection in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(2), 144-155.

Aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy and built upon work of others such as Dewey (1966) and Kolb (1984), this model was developed at McMaster with the goal to guide, assess, and evaluate students’ higher order learning through experiential education in McMaster’s Sustainable Future Program.

Instructional resources, including a handout of the RLF rubric, a guide to using the RLF, and a reflection-writing workshop video can be found below:

Sources:

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. The Free Press.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Reflection assignments

This section includes different types of reflection assignments that could be used by instructors to integrate formal reflection into their courses.

Level 1 Assignments – These assignments are for learners that are brand new to reflection. Level 1 activities are highly structured with instructions to better familiarize the user with the process of reflection.

Level 2 Assignments – These assignments are for learners that grasp the fundamental principles of reflection and are ready to dig deeper into their experiences. Level 2 activities are structured to be conversational in encouraging critical analysis of learning.

Level 3 Assignments – These assignments are for learners that are experienced with reflection and are ready for a thoughtful look at their own professional identity. Level 3 activities are less formal and more open-ended in structure to draw out the different ways that learning can transform us.

Name: Three-staged Reflection Worksheets

Description: Structured handouts with explicit instructions for students to engage in reflection aligned with an intended learning outcome of the course. Three handouts are included to be administered at the beginning, midpoint, and end of the course. These handouts follow the McMaster Engineering reflection model. Note: for courses that are one academic term in length, it is recommended to only use Worksheets 1 and 2 to prevent student fatigue.

Recommended Class Size: Small, Medium, Large.

Name: Reflection Short Essay

Description: Reflections prompts for students to address in a 350-500 written essay using the What? So What? Now What? framework.

Recommended Class Size: Small, Medium.

Name: Project-based Reflection

Description: An assignment intended for reflection on a group/individual project with prompting questions intended for students to reflect critically on the knowledge they applied and skills they developed during the project.

Recommended Class Size: Small, Medium.

Name: Job Interview Video

Description: Students submit a 3-minute video of themselves discussing a critical incident related to their course and how it has helped them prepare for the professional world.

Recommended Class Size: Small.

Repository

Have you created a reflection assignment that worked well, and would you be interested in adding it to our assignment repository? Sharing your reflection assignment templates can help others create assignments for their courses. If you are interested, please email hanses2@mcmaster.ca.