This International Women’s Day, we share the story of Sogol Akef, Head of Engineering at The United Nations World Food Programme, who found her passion for humanitarian work during her civil engineering classes at McMaster.

From a young age, Sogol Akef knew she wanted to be an engineer to make a difference.

“Being raised in a country with conflict, neighbouring Afghanistan and seeing refugees coming to Iran, I always wanted to rebuild and help people,” she says of her childhood in Iran. In the mid-1990s, her family immigrated to Toronto, where they still reside.

In 2000, after finishing a seismic engineering and transportation degree in Japan, Akef returned to Canada and wanted to do something else.

“I actually wanted to go into architecture, but I couldn’t draw,” she recalls with a laugh. Instead, she began her civil engineering education at McMaster University after being drawn to the labs and faculty members who were passionate about global issues.

I think civil engineering was always in my blood, but my classes and projects at McMaster really formed the way I thought about engineering, sustainable development and working in the humanitarian sector.

In one of her projects in Prof. Brian Baetz’s class, she recalls doing field visits and proposing sustainable development strategies for the community, including rooftop gardens and rainwater catching systems.

“That was the first time I was forced to think about these things – that was when I thought, wouldn’t it be cool to work in an area where I can help people with food distribution and sustainable livelihood?”

Akef shares her story via Zoom from a United Nations compound in Kabul, Afghanistan, where she now lives and works as the Head of Engineering for The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP).

WFP is the world’s largest humanitarian organization with the goal to eradicate hunger, one of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2019, the WFP helped close to 100 million people in 88 countries who are victims of acute food insecurity and hunger.

Last year, WFP received the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.

“There’s an important link between conflict and hunger,” Akef says. “What we know is that food assistance and access to food hubs reduce conflict, and it’s the first step into peace and stability in the communities.”

Tackling food security and healthcare in a global pandemic

Akef moved to Kabul in February 2020, just as COVID-19 began impacting communities around the world. Countries like Afghanistan which suffer from food scarcity, natural disasters, security threats and less-established healthcare systems were ill-equipped to handle the fast spread of the pandemic.

“In Afghanistan, there are 16.9 million people in need of food. WFP estimated that there would be an additional three million people in need of food due to the socioeconomic impact of COVID-19,” Akef says.

“Here, people have to make a choice. Do they eat, or do they get infected? That’s part of the heartbreaking truth when you work in this kind of situation. Reducing WFP’s footprint in the early days of the pandemic wasn’t an option – we actually ramped up our efforts to reach as many people as possible,” Akef says.

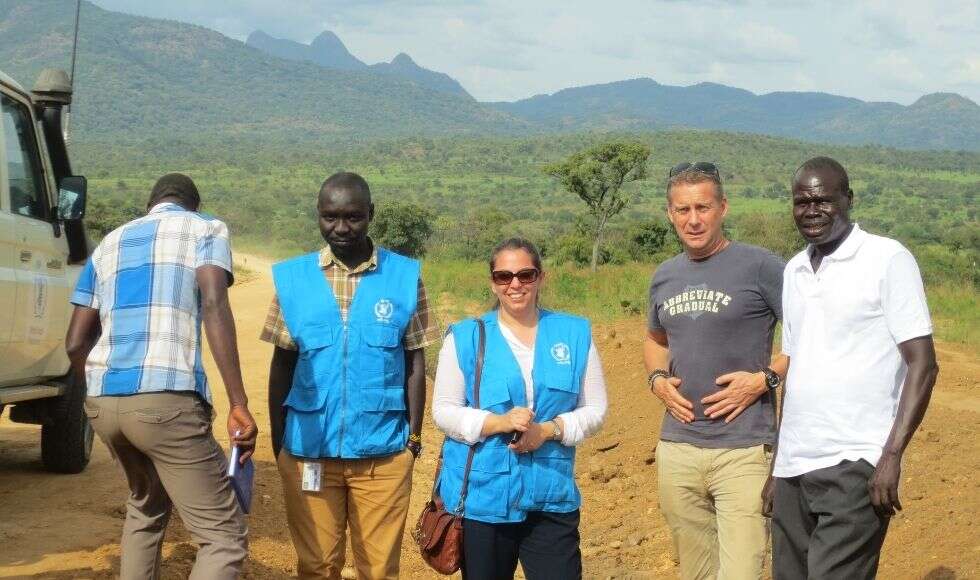

Over the last year, Akef led a team of engineers in improving access to food for millions of people – building roads and runways, warehouses, storage facilities and offices for UN staff. All while COVID-19 was rapidly spreading through communities where they worked.

There was a hospital in Kabul initially dedicated to care for patients exposed to COVID-19, but that hospital had serious challenges, Akef says.

“It was very important that we set up something very quick and accessible for UN staff and their families, so that staff would receive treatment if they were exposed or infected, and we could carry on assisting those in need of food,” she adds, noting that staff would otherwise need to be evacuated from Afghanistan to receive treatment.

In just four weeks, the team completely renovated an existing UN office space in Kabul into a COVID-19 treatment clinic. It was made “hospital-friendly,” with space and dividers to isolate patients, electricity rewired to support 24/7 ventilation, and steel shutters on windows to protect staff and patients from potential security threats.

Since opening its doors in September 2020, the team of 12 external doctors and nurses has treated more than 15 people from WFP and other UN agencies.

“The clinic is a good example of how crucial partnerships are to achieve the UN SDGs. It’s a small project but it makes a huge impact by partnering with UNHCR and other agencies, with the support of donors around the world,” she says.

“Everything we do, whether it’s making warehouses or roads, requires people coming together to achieve these goals.”

Hope for humanitarian engineering

Akef says she remembers the disbelief and joy when she learned of WFP’s Nobel Peace Prize.

“We have 20,000 people around the world in WFP and it’s a testament to the hard work they do and the sacrifices they make,” she says.

Knowing that what you do makes a difference in someone’s life is why I love humanitarian engineering. The roads we build in Afghanistan connects families to schools, mosques and gas stations. You’re ultimately impacting the lives of children who one day could become doctors, engineers, nurses, and giving women the avenue to sell products at city centres to provide for their families.

As the first and only woman to manage a team of engineers at WFP, Akef says she hopes to be a role model for up-and-coming engineers at WFP and beyond – the female mentor she never had as a young engineer.

“If you love learning new skills and a bit of adventure, I urge students to look at the humanitarian sector. There are so many opportunities and we need engineers with fresh perspectives,” she says.