Get close to the brilliant McMaster Engineering minds who are changing the world. Explore the cutting-edge research of our Fireball Family members and meet the innovative people “Behind the Big Ideas.”

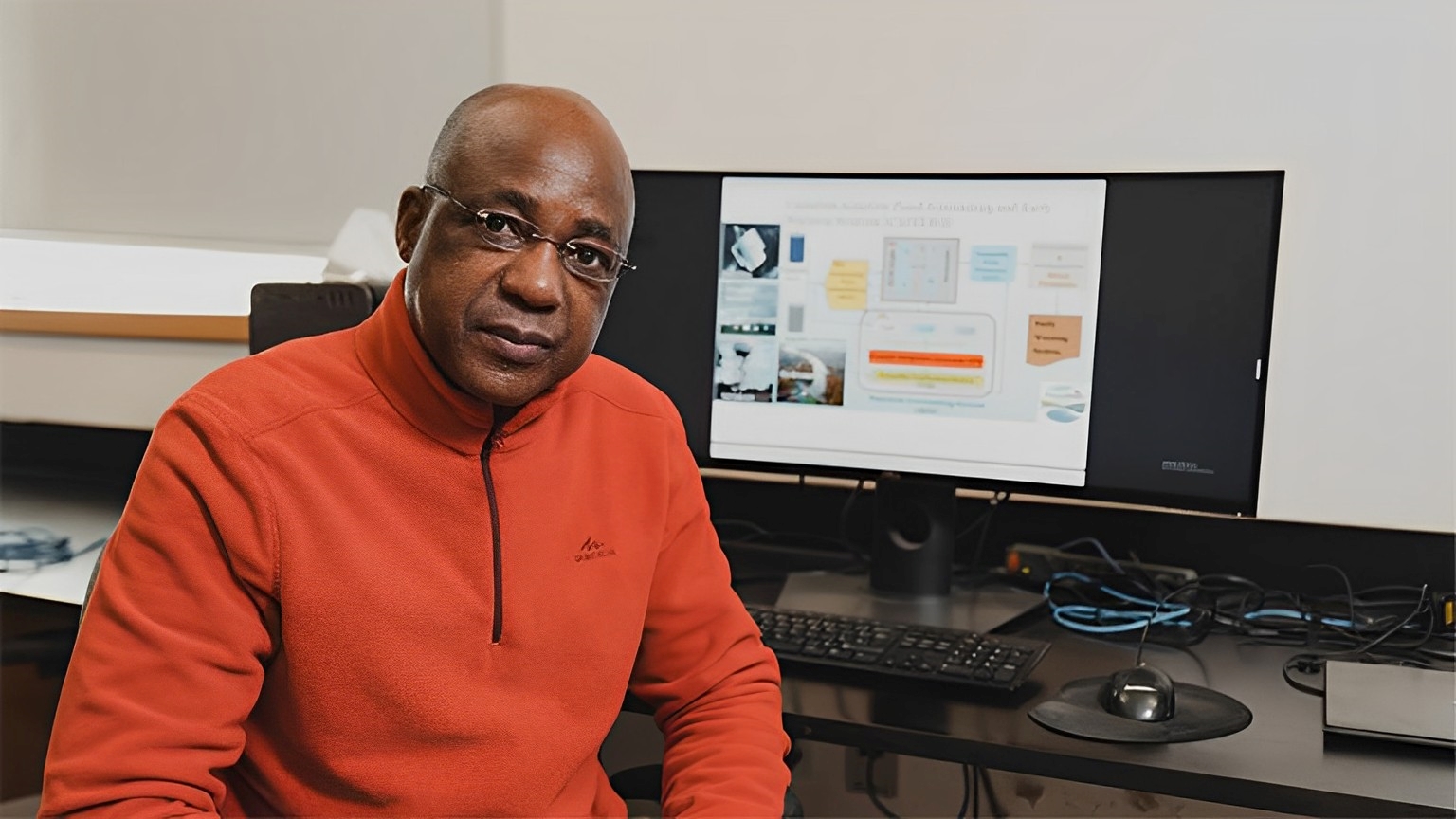

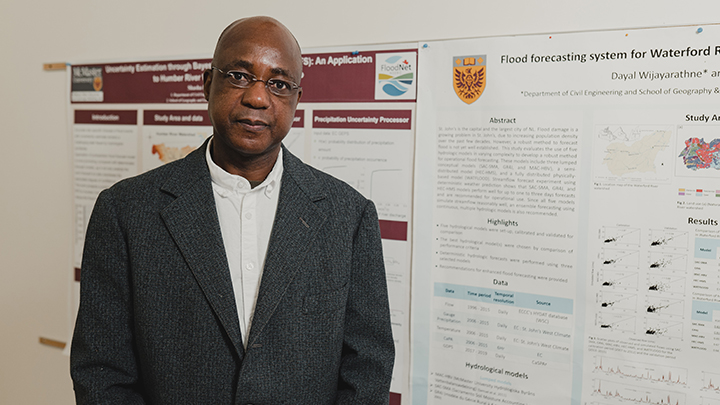

Paulin Coulibaly knows the world can’t afford a lack of certainty when it comes to flood forecasting.

Its critical nature drives Coulibaly, the director of FloodNet, to pursue a tool that would prevent the challenges involved with predicting the impacts of this extreme weather event.

He envisions a future where people across different levels of decision-making hold in their hands the power to better mitigate situations that are destructive and deadly.

The McMaster Engineering professor – working jointly across civil engineering and with the School of Earth, Environment and Society – and FloodNet are involved in developing a next generation flood forecasting tool that’s adaptive to Canadian geographic conditions.

Providing the right information at the right time to people that will be heavily affected by the flood. Being able to see on the screen what will happen in different areas in the city – that’s a tremendous opportunity for helping to save people’s lives, reduce the impact on infrastructural damage, and enhance planning as well.

Coulibaly says researchers are working to push this pilot system to the finish line. The Canadian Adaptive Flood Forecasting and Early Warning System (CAFFEWS) has been developed using significant data from Ontario, as well as British Columbia and Manitoba. Further testing, Coulibaly says, would be ideal in areas such as Quebec, Alberta, and the Maritimes to validate and expand its efficacy.

He explained that the tool is starting with the most advanced open data handling platform as its base – the sophisticated DELFT-FEWS system, a collection of modules designed for building a customisable hydrological forecasting system from water-leaders in the Netherlands.

The crucial issue is that flood forecasting accuracy doesn’t give much breathing room as it relies on the weather forecast, which Coulibaly says is not accurate beyond three days. If the initial weather forecast is off the mark, he says, its flood counterpart will be incorrect.

The FloodNet team is targeting the urgency of predicting situations as soon as possible, all the while ensuring the tool is user-friendly — keeping the foundational mathematics “behind the scenes” and a comprehensible interface up front so that it can be used in flood forecasting centres and by decision-makers across the country.

Coulibaly also envisions users simulating future events, enhancing the magnitude or changing the time before intervention, as well as evaluating information that led to the flood to see how different situations would have panned out.

“We would put the Canadian flood forecasting capacity at the forefront. We will be the ones using the most advanced tool.”

Coulibaly beams when he tells of his most memorable moments as a researcher so far. A tool that enhances the forecast of water level in reservoirs, initially developed as part of his PhD research, is still in operation today. Another accomplishment will hit the market soon – called DEMO, an advanced tool for evaluating and designing water monitoring networks. The software, initially funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada, will have international ramifications.

Climate change is only going to become increasingly critical, Coulibaly says. He referenced the recent floods in British Columbia, noting that nailing down the areas that would be critically hit is very challenging to forecast with today’s tools.

If you are in research, he said, “those are the things that keep you awake.”

John Preston, Associate Dean Research, Innovation and External Relations, recently sat down with Coulibaly to talk about managing flood risk in Canada, working with Global Water Futures and advocating for EDI at McMaster.

Coulibaly is part of the African Caribbean Faculty Association at McMaster (ACFAM), which is involved in a cohort hiring initiative at McMaster University with the goal of up to 12 appointments of emerging and established academics and scholars who will contribute to the advancement of Black academic excellence across all six Faculties.

“Our pursuit of EDI is simply from my viewpoint a pursuit of justice,” he says. “Whenever a systemic barrier is removed it makes our entire society more just.”

Paulin’s Gambit

Coulibaly’s affinity for meticulous calculations and predictions doesn’t just apply to his work – it also spills over into his play too.

The researcher is entirely captivated by the game of chess and shares this passion with his eight-year-old son, who has serious dreams of beating his dad on the gameboard.

Coulibaly remembers when he chased a similar dream – it’s how he got into the game in the first place.

He learned the game when he was 12-years-old, as part of a partnership with a priest in his hometown in Burkina Faso, West Africa.

The priest – originally from Latin America, but in Africa via the United States – preached at a church where the people spoke the local language. Coulibaly was able to span that disconnect; he had learned French early in life from his own father, who was a school teacher, and became a translator for the priest.

Aside from French, the priest and Coulibaly spoke another language with each other – that of Kings, Queens, and pawns.

“We played chess, and he told me that if you will beat me, you can have it [the chessboard] for yourself,” Coulibaly remembered with a laugh.

“And that happened. And this is how I got my first game.”

Coulibaly carried forward, teaching his friends, siblings and those at the university. He can’t imagine how many sets he’s owned in a lifetime, but always has at least two chessboards at the ready – not counting any opportunity he can get to play on a digital one.

His son recently led the charge to purchase a large board that could be used in the garden – perhaps destined to be the setting where he’ll finally tell his dad, checkmate.