Imagine being able to visit your physician, and instead of being given a one-size-fits-all treatment, you are given a specifically customized medication for your symptoms.

A team of McMaster University engineers has found a way to use 3D printing technology to create artificial tumours to help researchers test new drugs and therapies, which could lead to personalized medicine.

Currently, for researchers to study human health, testing is very expensive and time consuming.

Research to learn about diseases is typically conducted in laboratory environments, for instance by creating a single layer of human or animal cells — 2D models — to test drugs and how they impact human cells. Alternatively, animal models are used to study the progression of disease.

If realistic 3D cell clusters, with several layers of cells, can be produced that better mimic conditions inside the body, then this has the potential to eliminate the use of animals in testing.

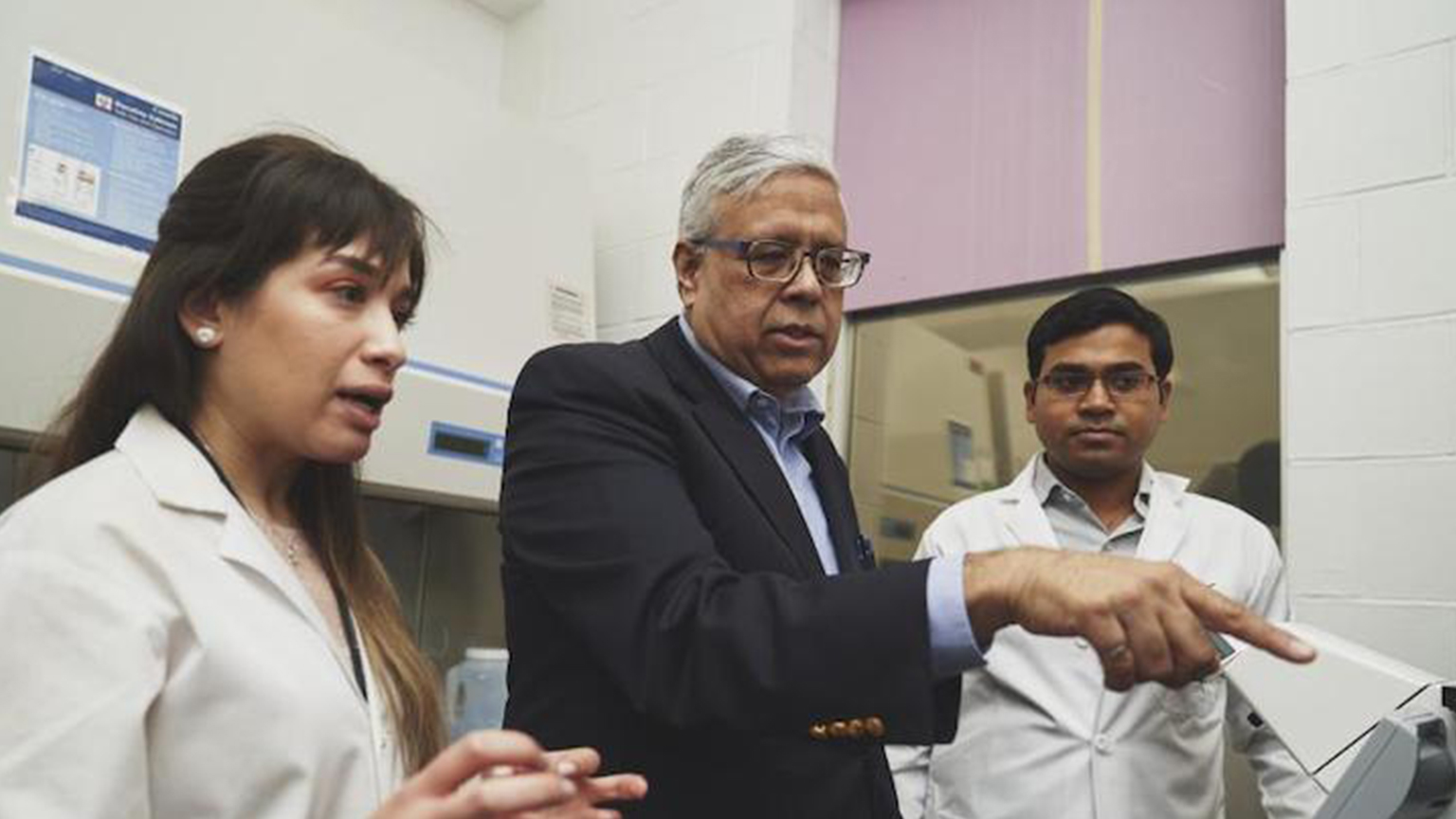

Led by Ishwar K. Puri, a professor of mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering, the McMaster team has developed a new method that uses magnets to rapidly print 3D cell clusters.

To do this, the McMaster team used magnetic properties of different materials including cells. Some materials are strongly attracted, or susceptible, to magnets than others. Materials with higher magnetic susceptibility will experience stronger attraction to a magnet and move towards it. The weakly attracted material with lower susceptibility is displaced to lower magnetic field regions that lie away from the magnet.

By designing magnetic fields and carefully arranged magnets, it is possible to use the differences in the magnetic susceptibilities of two materials to concentrate only one within a volume.

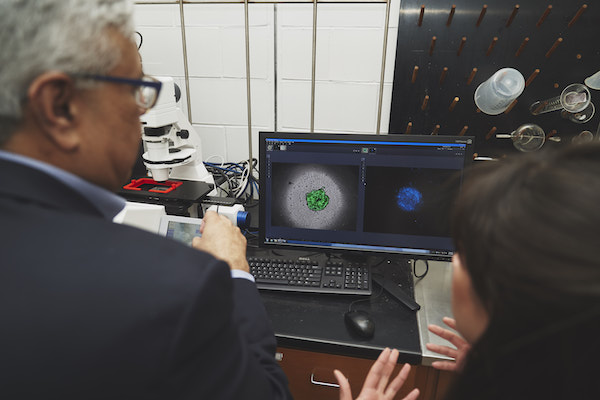

The team formulated bioinks by suspending human breast cancer cells in a cell culture medium that contained the magnetic salt hydrate, Gd-DTPA. Like most cells, these breast cancer cells are much more weakly attracted by magnets than Gd-DTPA, which is an FDA-approved MRI contrast agent for use in humans. Therefore, when a magnetic field is applied, the salt hydrate moves towards the magnets, displacing the cells to a predetermined area of minimum magnetic field strength. This seeds the formation of a 3D cell cluster.

Using this method, the team printed 3D cancer tumours within six hours. Tests were performed to confirm that the salt hydrate is nontoxic to cells, and they are now working on more complex bioinks to print cell clusters that can better mimic human tissues.

In future, tumours containing cancer cells could be rapidly created through 3D printing, and responses of these artificial tumours to drugs rapidly tested, with scores of experiments being conducted simultaneously. Printing human-like cell clusters also offers a future pathway for the 3D printing of multiple tissues and organs.

Their study, “Rapid magnetic 3D printing of cellular Structures with MCF-7 cell inks,” was published in the February 4 issue of Research, a Science partner journal.

“We have developed an engineering solution to overcome current biological limitations. It has the potential to expedite tissue engineering technology and regenerative medicine,” said Sarah Mishriki, a PhD candidate in the School of Biomedical Engineering and lead author. “The ability to rapidly manipulate cells in a safe, controllable and non-contact manner allows us to create the unique cell landscapes and microarchitectures found in human tissues, without the use of a scaffold.”

“This magnetic method of producing 3D cell clusters takes us closer to rapidly and economically creating more complex models of biological tissues, speeding discovery in academic labs and technology solutions for industry,” said Rakesh Sahu, a research associate.